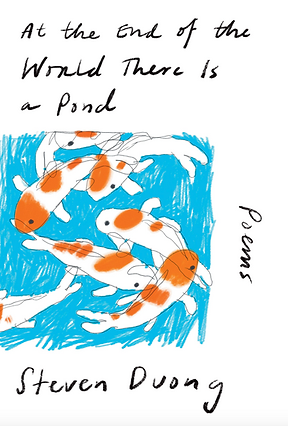

On At the End of the World, There Is a Pond by Steven Duong

.png)

At the End of the World, There is a Pond by Steven Duong

Sometimes I’ll take my daughter to an “independent” Zoo near me. We live in a rural area, and it’s the only one within an hour’s drive. Her favorite thing to do is feed the koi. There are well over a hundred, and the water boils with them. Next to their pond is a hand-painted sign asking guests not to throw coins into the water. This is the first association I made when I picked up Steven Duong’s debut collection, At the End of the World There Is a Pond, and the connection is fitting. A wish is asking for our lives to be moved in another direction. It is a kind of displacement. Money, too, is a displacement; money is a repository for all wishes. And people throw those wishes into a pool, teaming with koi, displaced from their home. At the End of the World… is a book about displacement: the displacement of migration, the mental displacement of drug use, and the ultimate displacement of death (individual and communal). In his stunning debut collection, Duong traces these displacements with a deft lyric style.

Migration is a wish that life will be more livable elsewhere. But that comes with a price. Your country is a way of understanding yourself; it is part of you, so something is excised when you leave. As Duong writes in the eponymous poem opening his book: “When my mother came here, she whistled a song / for the fish back home… / The line across her back marks / where doctors took her dorsal fin.” And what is home for the children of immigrants? It is the absence of an absence, which is perhaps why the speaker of At the End of the World... is always moving, in search of something he can’t quite articulate, beating his hands against the glass walls of himself. In “Lake Malawi Postcard,” one of a series of postcard poems in the book, Duong writes:

I’m trying to be a man with broad shoulders.

Things get heavy, Bee. Sometimes I lose my

shit in a cabin on the lake. Too many flies. Too many

bodies crash-landed in the dirt. I get antsy. I take

my drugs dutifully with my breakfast, wedding the pills

that won’t take to the eggs that won’t give. A man

can hope. A man can wilt his hands into fists, his fists

into prayers. Some things a fist can do, a prayer

wouldn't dream of. But is the opposite true?

The opposite of Coke is Pepsi. The opposite of saying

is doing. When all is said & done, I resay, redo,

refresh the page until it crashes. I get heavy,

Bee. I’m trying to be a man with hope in hand.

Here, the speaker seeks grounding, to be “a man with broad shoulders.” He wants to move from the reactive action of clenching his fists, to a future-oriented one, like prayer. He is overwhelmed, antsy. He wants direction, wants to stop hitting refresh on the same page, wants to stop circling like the fish in his father's ten-gallon aquarium.

This desire for grounding is seen in another series of poems in the book, all titled “Novel.” They center on the speaker’s struggles to write down his story. In one he writes:

I’m still looking for a title. Something sharp.

Plaintive. Load bearing. The first one, which

I won’t write here, couldn’t carry me where

I had to be. It left the mother & son unmoored,

just as my own name unmoors me from what

came before...

By crafting the right story, the speaker hopes to create a tether to the world. However, the effort is futile. In the final “Novel” poem, Duong writes:

Not even in my dreams is it done, its plots

set, its characters lost in thoughts I once

thought. There’s still that long ugly stretch I forgot

to set down (i.e., chose not to recall), the parts

that constitute the Real Thing & insist

on remaining parted, even after the limp

third act & the long-expected relapse, the mother

losing her mind, the son minding her loss,

& all those lovely sentence fragments chained

like daisies to their throats. No. Most nights,

I dream of doors in a long hallway. I know

that one belongs to me, that when I step

through it, I will arrive finally at my life.

Just not tonight. Perhaps another night.

The novel is the promise of a story that will hold the speaker; however, it’s a promise that can never be delivered while Duong is alive. It is a chalk outline for a living body, a door at the end of a hallway that will take a lifetime to walk.

This futility leads to drugs, another displacement, as a way to leave the self. “[T]here are pills you take & pills that take you,” Duong writes in the poem opening the book. Later, he closes “Ode to Future Hendrix in the Year of the Goat” by stating, “May we one day grow as / full as the moons behind your tongue, a couple // grams of white & some purple to chase it home. / No past. No future. Just two bottomless cups.” Drugs are a dissolution of the self, a way to stop swimming and just dissolve like a pill on a tongue. If existential questions plague the speaker, drugs offer a way to stop existing. In “Oxycodone,” Duong writes:

Tomorrow is a pond at the edge of the sea.

Tomorrow, my feet in the pond, yours in the sea,

we become little doors, always opening.

I will always open my door to you

In the hours between darkness.

Drugs offer the opposite promise of narrative. They untether the self from the world. Drugs are the sea a pond can drain into. But, unlike narrative, they are able to deliver on their promise. In a hallway of locked doors, they are the one that always opens.

And, drugs aren’t an unreasonable choice in a world hurtling towards its own dissolution. The speaker doesn’t have to close his eyes to imagine “when the earth enters its blue phase / & the rivers leave their beds / unmade…when we kayak down the road / to loot the pharmacy / named for the oligarch.” Even in his poem “Best Case Scenario,” “[t]his century ends underwater.” Our art won’t save us: “The bones of / the poets, / still belted to their Camrys, [will be] settled by runaway / guppies.” However, if Duong’s gaze into the abyss feels nihilistic, remember that he’s looking for a door. He closes “Extinction Event #6 at the Shanghai Ocean Aquarium” with the following:

Imagine a door

at the bottom of the ocean. What of us escapes

the end? What scuttles into the light, tongueless

& proud of it, tearing up the seafloor with

its thousand stupid limbs?

Futile or not, Duong is searching for the right narrative, one that can carry both him and us collectively, forward. A narrative where we stop drifting and stand broad shouldered. A narrative where we unfurl our fists into hands.

The final thread in At the End of the World... is a series of poems titled “Tattoo,” which appear in the book’s closing section. In a life of perpetual displacement, it’s the way your body has been marked that’s permanent. Duong writes:

I’m still easing into this bastard love.

I draw Clay a cloud & a map & when

they say, How about a cloud map, I whip

one right up. A cloud field & a big cloud

sea. A road from Cloud A to Cloud B. Meaning

nothing, really. All I know is Clay loves

these small things & is willing to live forever

with how I imagine them. Every few days

they draw a map for their friend Trevor & Trev

sends back a poem. or vice versa. I barely

know them but it makes me so damn happy. All

that back & forth. I carve clouds in red & black.

I imagine them floating to Nashville, Portland,

Baltimore, fat with the sort of rain we live for.

Tattoos are a map. They show your path from A to B. Tattoos are a picture of the line a person made. Interestingly, despite the speaker having traveled extensively, the speaker chooses to ground himself in other people instead of a particular place. This is why so many of the poems in At the End of the World… are epistolary. And the tattoo poems are no exception, reading like love letters to the speaker’s friends. For Duong, tattoos are a map of human connections, even if those connections are no more than roads between clouds, floating over a pond at the end of the world.

It’s rare to come across such a fully realized first collection. Some poets succeed because they create their own idiom, and some poets succeed because they so uniquely inhabit an idiom. Duong belongs in the latter category. Duong’s skill is seen not in the ways he reinvents the lyric, but in what he can do with it. The vivid imagery, the reverence for the sound a word makes, the ending which takes all the air out of a room are all there, but Duong’s skill is seen in the unique lyric I/eye he has cultivated.

Matthew McBride / August 19th, 2025

.jpg)

Matt McBride's work has recently appeared in or is forthcoming from Action, Spectacle, Collidescope, Conduit, The Cortland Review, Figure 1, Guernica, Impossible Task, The Laurel Review, The Missouri Review, The Rupture, Rust+Moth, and Zone 3 among others. He is the author of one full-length poetry collection, City of Incandescent Light, published by Black Lawrence Press in 2018, and four chapbooks. His most recent, Prerecorded Weather, co-written with Noah Falck, won the 2022 James Tate Prize and is available at SurVision Books. He can be found online at mattmcbridepoetry.com and matthewdmcbride.bsky.social.