Review of Ashley M. Jones’s Lullaby for the Grieving

.jpeg)

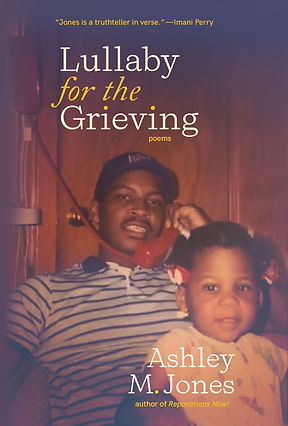

Lullaby for the Grieving by Ashley M. Jones

How would you aestheticize grief and haunting? What sorts of challenges to narration, composition, and history do writers adhere to or resist when grappling with the primacy of an event (past or present)? How do we honor spirited visitations? Do we ever risk blunting the experience and memory of ghosts and the ghosted by attempting to speak to and reproduce the psychic circuitry germane to the relation between the living and the dead in linear terms, using market-safe conventions?

This brings me to a discussion of Ashley M. Jones’ latest poetry book, Lullaby for the Grieving. Books can inspire, anger, bewitch, open, stagnate, tease, confound, point to and much more. Jones’ collection stirred in me questions about discourses on personal grief as they pertain to the loss of family members while meditating on black culture, joy, ingenuity and survival among black and other oppressed communities navigating inequality.

Jones employs the acrostic, prose poem, English (Shakespearean) sonnet, crown of sonnets, villanelle, contrapuntal, and free verse poetic forms with, at times, strict attention to prosodic measures like rhyme scheme and syllabics so that some of the poems are hymnal-like in their singing. The end rhymes in “Hoppin John: A Blues,” for example, conjure the sonic qualities of Langston Hughes’s poetry though maybe without the satirizing underbelly and subversive critique common in a Hughes poem.

this meal is tender medicine, ready

to heal what keeps us broken, to unyoke

ourselves away from helpless and enslaved.

we slice we sear we simmer and we braise

Other poets who come to mind are Countee Cullen and Claude McKay for their commitment to metrical verse.

The voice in Lullaby for the Grieving is that of a sharply critical, undaunted and prayed-up black woman whose religion is bound to the work of calling-out forms of anti-black racism while simultaneously meeting forms of black pathologizing with examples of individual and collective adaptability. In “All God’s Children Got Wings,” the speaker turns an historical account of Ann Williams whose death by suicide in 1815 (having jumped from a third-story tavern to protest separation from her family in slavery) becomes an allegory for thinking about flight and modes of freedom.

By taking up the theme, Jones’ book enters a conversation about strategies for resistance. Is death preferable to shame, dishonor, and indignity? In the Igbo tradition in southeastern Nigeria, suicidal ideation is condemned as a sacrilegious, self-serving offense that hampers community and mars God’s creation. On the other hand, the justification for suicidal feelings and death by suicide is often shaped by personal convictions as is seen in the recent example of Aaron Bushnell, self-immolating to protest U.S.-backed support of a genocide in Palestine. The Buddhist monk, Thích Quảng Đức’s 1963 ritual by suicide would be yet another example of the way one might agitate for freedom given the normalization of colonial, imperialist violence. Such strategies could account for the personal will or resignation of young people whose “private” demons are shaped by systemic forces or the ways we are sometimes socialized.

Then there’s “What It Really Is,” a punch in the face acrostic searing as the clot that calls itself America! Rigid as pulmonary embolism. CRT’s critics are chided for their willful ignorance about the cause for an interdisciplinary examination of the root causes of interlocking oppressions. In “Love and Happiness,” we have a nod to the sultry sounds of Al Green. The anaphoric repetition of Let’s stay is a play on a line from another one of Green’s hit singles, “Let’s Stay Together.” The poem is an elegy for the speaker’s friend and former co-worker Daphne Bowman Powell. The solidarity between these two is electric in-between counting numbers and shoring up reports. Punning on the word morning is an occasion to meditate on sorrow and new beginnings.

Perhaps more difficult to parse for me are the ways one approaches aesthetics, and the methodologies used to mine a subject like the omniscient hold that ghosts sometimes have on our lives. If Jones’ collection is a songbook of sociocultural discourse vis-a-vis the lyric, then it is often deliberately interrupted by what the poet refers to as grief interludes. In the middle of teaching and poeting, the speaker in Lullaby for the Grieving mourns the loss of her dad. In the opening “Grief Interlude,” in a direct address to the father, the speaker is left with the lacunae that is her dad’s absence: “I question the air. The spaces between the/leaves … I want to feel human again. Now,/a shell of flesh in the wind. Where did you go?”

Death defamiliarizes. The questioning, the unraveling, the dissonance that a hole in one’s life has on his or her or their sense of self is entirely relatable. If I hold one criticism, maybe it is that poets entrenched in the uncanny, the often-ineffable physical event of one’s passing, bear an obligation to carry the paranormal experience at the level of language itself. Jones’ book is at home with a logocentric view of the primacy of language and narrative convention which is befitting of the tonal registers that the poet employs to shine a light on injustice, and for which she will not compromise. I get that! I love that.

Whether the deployment of popular conventions is best defined as deference or submission to market forces is beside the point. These conventions do lord over U.S. literary art production, making it less attractive to engage an oppositional poetics that bespeaks the increasingly strange experience many of us are having in the belly of Babylon. Lullaby for the Grieving is a warm blanket pockmarked with spurs that the speaker wastes no time in plucking off one by one to sing, at times, a sorrowful and jubilant song of adoration for her people!

Richard Hamilton / August 12th, 2025

_JPG.jpg)

Richard Hamilton was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey and raised in the American south. A poet and critic, he holds the 2023–2025 writing fellowship in poetry at the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics at the University of Pittsburgh. His poetry criticism has appeared or is forthcoming in Rain Taxi, Blackbird Journal, and Callaloo Magazine. Richard holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Alabama.