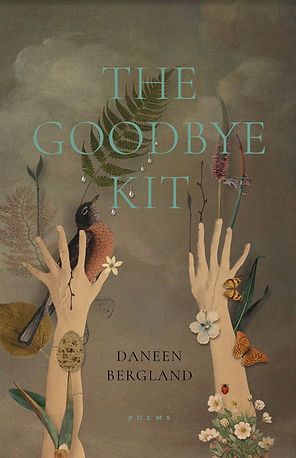

The Goodbye Kit by Daneen Bergland

.jpg)

The Goodbye Kit by Daneen Bergland

If Daneen Bergland's debut poetry collection, The Goodbye Kit, had a single throughline, it might be this: yes, the world is ending, and yes, it's our fault. Take your pick of apocalypses; of course there are ecological concerns, of endangered species both animal and plant, which Bergland writes about with a deft, lush, self-aware voice and striking lyricism, but the speaker in this collection is at the center of a number of worlds.

In terms of the collection's strong eco-leanings, Bergland warns the reader from the very first poem, "Animals Invaluable to Epidemiologists for Tracking the Spread of Disease Will Appear to us as Angels," that "These will be among the signs there's no going back: / A string of disembodied wings at your feet form a path." And it's clear that in this book, there is no going back. Ecological ruin is an eventuality, not a vague worry. But even in the shadow of a dire future, Bergland skillfully juxtaposes the real, the tangible, with the sacred: soap operas will leave us and bedbugs "make an epic comeback," while a bat could be either "carrying a disease / or a message about the sovereignty of flesh."

In "Zoology of Desire," the speaker grapples with the surprising action of encountering a beaver even though she's on its own turf, and the surprising physicality of the animal. The speaker draws attention to her attempt to view and be part of nature, evident in her excursion, and how she later has to "wash my hands / and kill the wilderness / inside the curled snake of my guts." Bergland is acutely aware of the choices we make and how we choose to interact with nature, as the speaker notes that she plants "what wouldn't grow here / without me." Here, then, are a few of the worlds these poems inhabit: speaker as witness to dying planet. Speaker as lover. Speaker as mother. Speaker as spiritual question-asker. Speaker as surprise, always. Bergland chooses her subjects and perspectives carefully, like a magician performing close-up magic. You think your eye is on the trick, and suddenly there's a quarter behind your ear.

Take "Fugue for Insects, Animals, and Vegetables" as an example, as it subverts the form of a fugue poem. As Alina Stefanescue notes, in a fugue poem, "different voices begin by imitating each other, but gradually diverge and become unique." Bergland's poem doesn't describe animals as they "live among us," as the poem contends; throughout, the speaker deals with animals in an ambiguous state of maybe-life-maybe-death, moving from spiders "asleep or dead" to whales, which "arc beneath us," to cats "sleeping their lives away." The speaker is active; she gardens, fights squirrels, and watches herself in the mirror. Seeing her reflection, she touches her breast, noting that due to the mirror image, "it is not the one / I try to touch." The repetition in this fugue is not of words or phrases but actions: ambiguously alive animals, the speaker trying and failing to make an impact. And it's not until the end of the poem that we find another layer of the fugue, as a literal song: "the night cricket plays his tiny violin / and feels sorry for us all." The reader searching for the fugue's repetition finds instead the poet playing a funeral dirge.

Consider also that cricket, the size of it, and how Bergland deftly manages to zoom in on small, often overlooked pieces of the natural world even as she tackles heavier concepts. In her first of three Eve poems, "Eve Wakes Up After the Fall and Picks Up Her Phone," the title character reads about other falls: a child, a baby sloth, a whale. What if, the poem asks, Eve's "fall" was a physical drop, and what if the gift of god is gravity? Later, in "Sometimes Eve Gets Drunk Enough to Forgive Herself," the speaker's forgiveness highlights humanity:

Sometimes we like to watch the weather happen

on a computer screen or spy for weeks at a time

on a bowl of eagles sleeping.

Eve acknowledges future extinctions but also mourns the inevitable loss of comfort: the way a house keeps its inhabitants safe; the ease of using YouTube to learn about butterfly chrysalises. Sure, there's some regret in "I wish I knew less," but not all the way: ". . . unlearning is not the same / as being unseduced." Choice rears its thematic head throughout the collection--what do we choose to plant or preserve, and what do we choose to witness? And in the case of Eve, the choice to give her agency to forgive herself, and not request it of the reader.

In the collection's final poem, "The Goodbye Kit," the speaker seems to be compiling a sort of go-bag for the end of the world, and decides between what's important to preserve, and what can be forgotten. The list of items to keep is distressingly short: heirloom tomatoes, a book of matches. What is the point in holding onto "maps now, or cats, or panic" when the ending has already been decided? There is no course change here, only an indication of what will be lost, from the achingly human--"those daughters on the honor roll"--to the divine loss of "God's bottomless dread / where once there had been bottomless desire." What's left is an exhortation to prepare the home for exit; not a harsh command, but an inevitability:

Time to cover the mirrors.

Time to tuck in your feathers. Time to relinquish

all your plastics and let the sea fill.

Nothing's calmer than a husk,

its soft brush with death.

Review Notes:

Alina Stefanescue quote may be found here: https://www.alinastefanescuwriter.com/blog/2019/9/3/fugues-sonatas-and-musical-notation-in-poetry

Pamela Manasco / July 21st, 2025

.jpg)

Pamela Manasco is a poet and English instructor at Alabama A&M University. She is the recipient of an Alabama State Council on the Arts poetry fellowship, and the 2024 Stephen Meats Poetry Prize. Her poetry has been published in The Louisville Review, Bear Review, Split Rock Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Madison, Alabama with her family. You can find her on Instagram and Bluesky @pamelamanasco, and via her website: https://pamelamanasco.com.