Review of Steven Leyva’s The Opposite of Cruelty

.jpg)

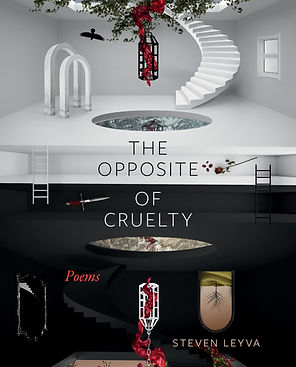

The Opposite of Cruelty by Steven Leyva

In Steven Leyva’s The Opposite of Cruelty, Creole is not only a matter of genealogy but a structuring principle applied to the book itself. He writes in the second section’s opening poem “Double Sonnet Instead of an Introduction”:

“Nearly every continent is in your genealogy:

You are Black. You come from a Creole

so old no one can skin the pear of your first

language…”

This is a starting point for Leyva, but he does not treat métissage merely in terms of racial heritage. Constellating poems that range across Césairian negritude, Grecian myths, hip-hop, and anime, his second collection draws from an array of source material and refuses distinctions between highbrow and lowbrow culture. What results is a book-length hybridity that is as eclectic in its assemblage of references as it is diverse in its formal and generic experimentations.

Leyva writes sonnets, aubades, odes, and pastorals, to name a few, but he also is in conversation with pantoums. “Halo,” one of the standout sequences in The Opposite of Cruelty, follows a procedure in which the last line of each section is rehashed as the first of the next, often by redistributing where the syntax is broken. The sequence, moreover, reaches its apex in the fourth section when repetition is extended to the entire section, of which below is a sample:

“After asking for a lover’s number, the deft touch of a porch light across the cheek

is like the angler fish, whose luminosity and ugliness coexist. Amen.

After asking for a lover, number the deft touches of a porch light across the cheek.

Is there enough to fill the wolf’s mouth and see what it eats? Amen,

after asking for a lover’s number. The deft touch. A porch light across the cheek

is like any other kiss. Tender but never enough. Shameless. Amen.”

This recursion is nothing if not inventive, playing with shifts in emphasis and meaning by displacing a comma or introducing a new end stop. It is a meditation on difference and repetition, on the ritual of return and reprise. As a method, it evinces a poiesis open to the contingencies of reproduction and slippage like a formal equivalent to the genetic variation that constitutes a hybridized identity.

But it isn’t only on the level of form that Leyva explores multiplicities that orbit singular foci. For The Opposite of Cruelty establishes the poet as a harborer of diverse influences who’s indebted in equal measure to decorated writers such as Derek Walcott and Wanda Coleman as to fictional characters like the X-Men and the Black superhero Static.

In “Ode to Static,” he writes “Static you were a milestone // for kids like me, whose brown skin / ran the whole gamut of electro-spectrum,” odically celebrating the collective self-regard that Static made possible—“the mirror / [he] held up to our future.” It is a moving piece that similar to Leyva’s other pop cultural poems rejects the notion that sublimity is exclusive to traditionally ‘poetic’ subject matter; and as he shows in “Self-Portrait as Prince of the Fire Nation,” it is possible to write a perfectly serious poem inspired by Avatar: The Last Airbender.

To give you a fuller sense of Leyva’s range, in the course of The Opposite of Cruelty, he quotes from UGK ft. OutKast’s “Int’l Players Anthem,” he writes of shopping at Banana Republic, he imagines Bruce Wayne in his cave, and he harmonizes with the rhythms of Tejano music. If workshop wisdom encourages the poet to write what they know, Leyva answers this call in spades. For as he seems to well understand, these era-specific experiences are only ever entry points to the affective center of a poem.

The most breathtaking of these centers is in his “Ode to the Sword of Omens” in which he recounts watching ThunderCats as a child. The Sword of Omens, as Leyva explains in the notes, is a weapon wielded by Lion-O, the protagonist of the animated show; and as the poem’s central object, it functions like a red herring that distracts the reader from the speaker’s familial and psychological context until, little by little, the reason for the fixation emerges:

“…Sword of heroes,

what omens can you offer

that will sheathe the sadness

my mother wielded in a tithe?

Can you tell me how dark these steel

gray mornings will make my skin?

Can you tell me tomorrow’s

weather? Can you tell me when

my father will come home again?”

This is how opposites tip into each other, where levity becomes gravity and hope becomes grief; and in traversing the terrain from one polarity to the next, one is reminded of all that falls between. For as linguist Algirdas J. Greimas reminds, not-cruelty isn’t identical with mercy, and in Leyva’s second collection, not every poem is encapsulated by compassion, but each is restless in opposing what is cruel.

Won Lee / July 7th, 2025

.jpg)

Won Lee is a Korean-American writer and visual artist based in Chicago. He is a Litowitz MFA+MA student at Northwestern University. His work appears in Bellevue Literary Review, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Action, Spectacle, and elsewhere.