Poetics as Temporal Landscape: A Review of When the Horses by Mary Helen Callier

.jpg)

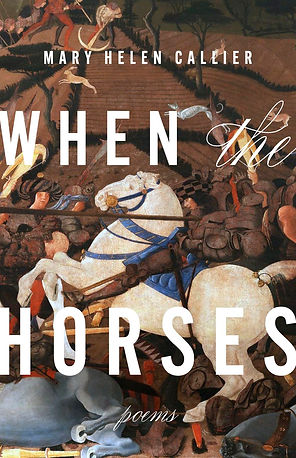

When the Horses by Mary Helen Callier

When the Horses, by Mary Helen Callier, is everything elegant and nothing simple.

Callier’s capacity to embed the ordinary in both linear and non-linear landscapes is a tour-de-force, a choreography of intellect rooted in the somatics of image and metaphor. Each poem is a world, and when interwoven into the body that is this collection, in seven numbered sections, I am left speechless and sated. The opening stanza of “Tonight I Think My Body Is A Lake” brings this home.

When you were young you swallowed a handful

of pills and walked outside to see

about the banquet. You didn't think there'd ever be

a way to live inside the world.

You fell. You heard a distant voice approaching,

as if from the opposite end of a tunnel.

The beauty of this narrative thrives in its simplicity and compression. Its dissociative tone amplifies its power and disembodied sensibility. The word “banquet” here is entirely unexpected. We are turned on our head as banquet and suicide are offered in the same breath. But the ordinariness of voice, coupled with a kind of hidden absurdity, pulls us to stay.

From the epigraph by Albert Camus, “One does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write / a manual for happiness.” to the final poem, Callier’s syntax and nomenclature glares at us with plainspokenness—so much so, we consider that what is being said must also be pointing to what is not. The tension of this dissociative underpinning straps us in. Her bare bone language is a distillation of a reality that is forever a hair’s breadth beyond reach—this starkness, always pushing the interrelationship of abstract and representational realms.

It is from this place of temporal ambiguity that Callier’s brilliance shines. In “Inward Journey”, “Hours and their years condensed/into a single viscerality”, temporality is transmuted into sensation. And later,

I kept walking through the garden

because the door to the house was still locked.

History heavy about me

like a shadow or a dog,

I’d watch it running off again,

then circling on back:

Callier’s meddling with interiority and exteriority maps, unmaps and remaps form and time, showing us our inescapable vulnerability.

In section IV of “Pondhawk” she begins— “Every beginning pulls into its chest the idea of itself / as an ending.” Beginning and ending embody each other. Here, time has a body, a chest, and so, is animate. How to consider this? Her answer is in the next line: “Isn't it great we don't have to talk about that?” Whew. And, ha! But then, she doesn’t let it go. A few lines later, “A hand on a thigh is a unit of time.” Back in the present moment. Body as anchor. Here, it is touch, connection, defining presence, offering that without the body as conduit, the desire for dissolution into the metaphysical is too alluring to resist.

This hunger to dissolve, to be other than a solid body, appears in several childhood poems. The child often yearns to be a substance undefined by the rules of time or form; air, water or even fragment. Such longing sears in its physical and intellectual pursuit to collapse the bridge between reality and fiction; as in from “Running Your Hand Through The Flame”:

All my life I think I've looked for

something to destroy me. When I was ten

I stood on the beach and watched dolls being passed

in the air through a crowd. I wanted to be light

and easily devoured. I was not. I was hard. Fixed

as a current. Dense as a forest in which no

paths are cut.

The collections’ final poem, “And Then When What You Knew Of It Was Over”, constructs and deconstructs presence through a confluence of speculative and real, images and metaphors overlapping past, present, and future tense. This is one of Callier’s superpowers, and it fills us with disorientation and disquiet. Yet, her economy of language convinces us that all of it must be true. Using language so seemingly ordinary, it’s as though she’s handing us an instruction manual on how to be present while saturating us with the quantum realities that hum and sizzle in and around us. Location and time become almost irrelevant. It is only presence that matters and the attention that inhabits presence. Through attention, we open to the myriad realms consciousness offers, bringing us closer to ourselves and what connects us. Callier’s quiet, stunning mastery teems with hunger, and promise.

You watched

one wave engulf another

as it led its way toward shore.

Stood up in the opening and the opening

kept opening and yes,

of course there was the voice

that said, Why not get up

and live and leave that leaving

lying there? Two muskrats swam away

carrying the great big nothing

left to say between us—

there was only wind,

wearing down another, paler

weather.”

Lindsay Rockwell / May 28th, 2025

.jpg)

Lindsay Rockwell’s work explores the shared landscape of poetry and the sacred. She’s recently published, or forthcoming in Poetry Northwest, Poet Lore, Tupelo Quarterly, RADAR, SWWIM every day, among others. Her collection, GHOST FIRES, was published by Main Street Rag, April 2023. She is the recipient of the Andrew Glase Poetry Prize and fellowships from Vermont Studio Center and Edith Wharton/The Mount residency.